Deuteronomy Seeds of Consolation: Open-Eyed Torah for a Friend

Parashat Vaetchanan (Deuteronomy 3:23-7:11)

For Lea Andersen, of cherished memory

Parashat Vaetchanan begins with Moshe deep in his feelings, as he recalls pleading with God to be allowed to enter into the Promised Land. He has devoted his life to his people, has endured hardship and frustration, conquered self-doubt and overwork, only to find that at the end of his life he will not get to see the task come to fruition. In Deuteronomy 3:25, early in the parashah, he says:

אֶעְבְּרָה־נָּא וְאֶרְאֶה אֶת־הָאָרֶץ הַטּוֹבָה אֲשֶׁר בְּעֵבֶר הַיַּרְדֵּן הָהָר הַטּוֹב הַזֶּה וְהַלְּבָנֹן׃

Please let me cross, so I can see the good land which is across the Jordan, that good mountain, and Lebanon besides.

You can hear in the first word of this verse “e’b’rah na” the way his plea almost catches in his throat—a sob, maybe, or the return of the stammer he overcame to grow into leadership. This is hard for him. Letting go is so hard.

When the answer to his supplication comes back from God, the same root letters—ayin, bet, resh—appear:

וַיִּתְעַבֵּר יְהֹוָה בִּי לְמַעַנְכֶם וְלֹא שָׁמַע אֵלָי וַיֹּאמֶר יְהֹוָה אֵלַי רַב־לָךְ אַל־תּוֹסֶף דַּבֵּר אֵלַי עוֹד בַּדָּבָר הַזֶּה׃

And God was cross with me, on your account, and would not hear me.

And God said to me, “You are too much. Don’t say another word to Me about this matter.”

Moshe never gets the answer he is hoping for; his transgression (aveirah, another ayin-bet-resh word) is deemed too great. Nonetheless, he composts his devastation at the lost opportunity and returns to his task. He doesn’t get to cross over, but nonetheless, he teaches us how. Sometimes disruptions—even catastrophic ones—can point the way.

This seems an apt message at this moment in the Jewish calendar. Parashat Vaetchanan is always closely paired with Tisha b’Av, the holiday commemorating the destruction of the Temples along with many other calamities throughout Jewish history. Tisha b’Av is the culmination of the season of admonition in our liturgical calendar, which traces the mounting horror of the three weeks from 17 Tammuz to 9 Av in the year 70 CE, as Roman invaders breached the walls of Jerusalem, laid siege, and eventually reduced the Second Temple to rubble.

Our observance of Tisha b’Av is leavened, finally, in the afternoon hours, when tradition teaches that Moshiach (The Messiah) is born. The seeds of consolation are planted in the soil of the worst catastrophes, watered with our tears. Within the week comes Shabbat Nachamu, the Shabbat of Comfort, and we are making our way—sobered, changed—toward wholeness again. It is our job to sift through the ashes of the ruined city and find a reason to go on.

Parashat Vaetchanan is bathed in resilience and faith. Despite his disappointment, Moshe takes up the thread of instructing the Israelites in how to acquit themselves to the longed-for privilege that he will never share in. He reminds them of mistakes along the way and of the slow-acting reward of staying true to core beliefs. In Deuteronomy 4:3, we read about the fate of some Israelites who backslid into idolatry. By contrast, the next verse teaches:

וְאַתֶּם הַדְּבֵקִים בַּיהֹוָה אֱלֹהֵיכֶם חַיִּים כֻּלְּכֶם הַיּוֹם׃

But you who stuck with Adonai your God, each and every one of you is alive today.

This verse, familiar from our Torah Service, bespeaks the value of holding on in faith when things seem to be crumbling all around you. Faith keeps us alive as a people, even as individuals die. Holding onto our essential beliefs, as articulated in Deuteronomy 5:6-18 in עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדִּבְּרוֹת (Aseret Hadibrot, commonly translated as The Ten Commandments), is fundamental both to our relationship with God and to our survival.

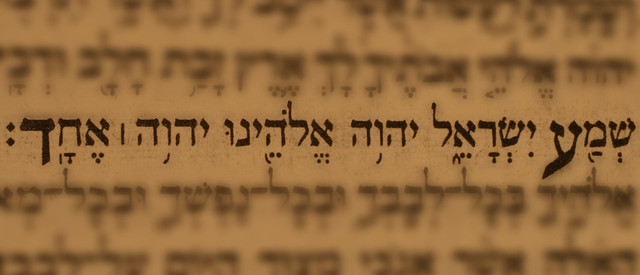

Then in chapter 6 we encounter possibly the most famous words in all of Jewish tradition, a stark declaration of faith, as succinct as a haiku (which it also is):

שְׁמַע יִשְׂרָאֵל יְהֹוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ יְהֹוָה אֶחָד׃

Listen, O Israel! Adonai is our God, Adonai is One.

(Deuteronomy 6:4)

In the Torah scrolls, there is something interesting with the calligraphy: the ayin of the word “shema” and the dalet of the word “echad” are larger than the other letters. There are no accidents or mistakes in Torah, only opportunities for deeper meaning to emerge. What could be behind these oversized letters? What magic do they hold?

Chizkuni (13th century France) suggests that the ayin is a reference to the way God created the world. Using gematria (Hebrew numerology), Chizkuni links the ayin to the number 70, and places each element of creation into a long chain of seventies: Israel is one of seventy nations, which is one seventieth of the number of four-legged beasts on the earth, which is one seventieth of the number of birds, and so on. Chizkuni writes, in part:

הקב״ה ברא מעש׳ו בעי״ן צי״ן

The Blessed Holy One engages in creation with ayin ayin.

Rereading Chizkuni, we might say that God created the world with both eyes open (another meaning for ayin is “eye”)—knowing that there would be pain and brokenness, and that through faith, humanity would fumble through and cope. With our eyes open, we can see the struggles of others. With our eyes open, we can see where our society can be more righteous. With our eyes open, we can see the beauty of this incredible planet, and pledge ourselves to treat it with tenderness.

Rabbinical student Lea Andersen, who died just a few days ago, was one of the most open-eyed people I have ever encountered. A gifted teacher, a warm pastoral presence, a passionate activist and more, Lea turned away from nothing and nobody. Her fierce and spacious Torah was a gift to the world, and those of us who knew her and learned from her, even a little, are sobered and changed because of it. Tragically, Lea will not see her life’s task come to fruition. I offer these teachings in her memory and in the hopes of inspiring more of us to see the struggles of others, see where our society can be more righteous, see the beauty of this incredible planet. Most of all, may we pledge ourselves to treat it—and one another—with tenderness.

Naomi Gurt Lind is a rising Shanah Gimel student at the Rabbinical School of Hebrew College, and is looking forward to rabbinic internships this year with 2Life Communities and Betenu Congregation. Naomi is an Innovation Lab grant recipient, a member of the inaugural cohort of Mayyim Rabbim fellows at Mayyim Hayyim Community Mikveh, and the editor of the 70 Faces of Torah blog. When she has a free moment, she enjoys solving crossword puzzles (in pencil!), writing divrei Torah on her blog, Jewish Themes, and playing Bananagrams with her spouse and their two genius children.

Ever considered the rabbinate? Join us for our fall Open House. Learn more and register here.

Ever considered the rabbinate? Join us for our fall Open House. Learn more and register here.