Jewish learning Of Comings, Goings, and Jewish Goodbyes

Parashat Beha’alotecha (Numbers 8:1-12:16)

I participate in morning minyan at my synagogue almost every day. The experience and routine is meaningful but generally unremarkable. But two moments stood out to me last week, which are related to the journeys—the comings and the goings—in this week’s Torah portion.

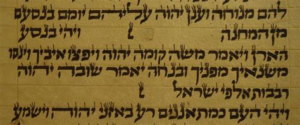

The first moment took place during a Torah service. Each time we read Torah, we bracket the Torah reading with the two verses from our portion, Beha’alotecha that are themselves bracketed by mysterious inverted nuns.

According to a discussion in the Talmud (BT Shabbat 115b-116a), the nuns either teach us that the verses belonged earlier in the Torah, or further subdivide the Torah into seven books instead of five. The verses read:

And it was, whenever the Ark was to march on, that Moses would say:

Arise [for battle], O YHWH,

that your enemies may scatter,

that those who hate you may flee before you!

And when it would rest, he would say:

Return, O YHWH,

[you of] the myriad divisions of Israel!¹

— Numbers 10:35-36

We begin each expedition of reading Torah by recounting our ancestors setting off on a journey, wishing for blessing and protection from danger along the way. And we conclude with a wish for return, perhaps a hope that the Divine presence that accompanies us while hearing and learning Torah should reappear. This conclusion of the Torah service and closing of the Ark, as a teacher of mine once said, can be considered a “doorknob moment.” This is the moment before parting, when one tells a psychologist, a doctor, a family member or friend, what one wished to say the whole time, but is only able to express when a visit is about to end.

What happened on that particular morning in minyan was simply that a congregant closed the Ark a couple verses early, instead of waiting until the final phrase, “chadeish yameinu k’kedem—renew our days as of old.” The rational part of me, having long since mastered object permanence, knew that the Torah was still in the Ark after the curtain closed, that a few moments wasn’t a big deal. But in my kishkes, in my gut, it felt like we were missing our doorknob moment, our opportunity to say or hear the most important thing, the last chance for a fond farewell.

Jews are famous for our goodbyes. The old saying about the British and the Yiddish claims that the British leave without saying goodbye, while the Yiddish say goodbye without leaving. On Shavuot last week, we chanted the story of Ruth refusing to leave her mother-in-law Naomi, saying, “Do not urge me to leave you, to turn back and not follow you. For wherever you go, I shall go.” (Ruth, 1:16) This week’s portion contains the last preparations for the trek through the wilderness. After all the counting, the offerings, and the marching formations, we’re finally about to leave Sinai. One midrash envisions the Jewish people running away from Mount Sinai with joy, like the proverbial child fleeing school to avoid more work, or more commandments. But I picture our ancestors being so reluctant to leave this place of revelation, this tangible, majestic symbol of God’s presence, that they may well have wished to linger beyond this year of encampment. And right before the journey begins, Moses’ father-in-law drops the bombshell that he will not accompany them, that he will return to his people in Midian. Moses pleads with him not to leave. While the commentators and midrashim imagine what happens next, we readers are left without knowing how this attempted leave-taking resolves.

This is the season of graduations and ordinations, when students of all ages are finishing the school year, preparing to journey on to more growth and learning, to new ways of being of service to the community. Each of these celebrations is also a loss, a farewell to fellow students and teachers, to places and communities. Though friendships and memories may be preserved, the communal experiences will not remain the same.

I was thinking about our sojourns and Jewish goodbyes during a minyan last week that I will never forget. A dear member of our community—optimistic, generous, goodhearted, a person who held babies at kiddush so that their parents could eat, helped twelve and thirteen-year-olds wrap tefillin, and made breakfast every Friday morning to encourage minyan attendance and camaraderie—has late-stage cancer. Since he could no longer come to shul, his friends organized minyan at his house. When the day came, he didn’t have the strength to come downstairs. He sat by the second-story window so he could see and hear and participate in the large minyan that had gathered on his front lawn. This gathering was at once a celebration of a journey, an expression of prayer, and a chance to say goodbye, part of a series of doorknob moments, of letting him know how much we love him, have been affected by him, and will miss him.

As we read about the journeys of our people in the desert this week, the comings and goings of the Ark of the covenant, and the feelings of hope, excitement, and loss that these journeys might entail, may we be inspired to keep our Arks open as long as we can, to connect to Torah and to other people as fully as possible, and to continue the proud Jewish tradition of lingering goodbyes, of refusals to leave, and of making the most of each moment.

Please email the author if you’d like to share any feedback.

Ken Richmond is the co-senior Rabbi of Temple Israel of Natick and has been serving as Cantor there since 2006. He received s’micha from Hebrew College’s Rabbinical School in 2021. He enjoys playing klezmer music, speaking Yiddish, hiking, and kayaking.