Rabbi Justin David Judaism and the Death Penalty

Like me, I imagine that you took some time to sit with the decision of the federal jury in Pittsburgh to impose the death penalty on the gunman responsible for the 2018 massacre at the Tree of Life synagogue. With our array of relationships to this horrific event and our own life circumstances, I imagine this news elicited a range of responses, thoughts and questions from you.

Given the dimensions of this tragedy, and the complexity of the sources in our tradition, I was surprised to see how relatively little attention the Jewish press gave to any conversation about Judaism and the death penalty. The Forward did host a podcast featuring a range of rabbis and scholars, but nothing in the way of a sustained consideration of the sources and this current moment. My hope is that some brief and very incomplete thoughts here provide ideas for your ongoing reflections.

My personal conviction is that execution in a democratic society is cruel and unjust, particularly given the legacy of racial violence in America and the history of deploying the death penalty disproportionately against African Americans. In recent years, I have found wisdom and been inspired by the groundbreaking work of Bryan Stephenson and his organization the Equal Justice Initiative, portrayed in his book Just Mercy. Stephenson’s line of inquiry and activism, built upon decades of documentation and research, is now reflected in the decision by the US Justice Department to impose a moratorium on federal executions.

Nevertheless, I find that I cannot dismiss the responses of families who lost loved ones in that unimaginably horrific event, and who now find in this decision a measure of peace and an expression of justice. I see the issue very differently from them, but I also understand their nechama as real. If I had experienced what they did, would I view the jury’s decision the same way I do now?

And yet, I believe it’s important to note how some of the victims’ families, as well as communities and Jewish leaders in Pittsburgh, have expressed their opposition to the death penalty, even in response to the act that shattered their community and individual lives.

Going back to rabbinical school, I remember what a revelation it was to learn that that the biblical phrase that prescribes capital punishment, “mot yumat,” was not understood as a foregone conclusion, as in “one shall surely die.” Rather, I learned that the peshat was more accurately rendered as a legal formula, “one shall be subject to being put to death,” requiring considerations and standards of evidence left out of the text.

As a student I also had the great privilege of studying in Jerusalem with the great Bible scholar Moshe Greenberg, who viewed the Torah’s statements regarding the death penalty more as statements about the supreme value of human life rather than as actual commandments to execute a murderer. For Greenberg, the statement towards the end of the flood narrative (Gen. 9:6), “ha-shofekh dam ha’adam, ba-adam damo yishafekh, Whovever sheds the blood of a human being, by a human being shall one’s blood be shed” is not a license for revenge. Rather, it is a moral formulation, stating with poetic and dramatic force that human life is invaluable as created in the image of God, as the statement concludes, “ki b’tzelem elohim asah et ha-adam, For in the Divine image did God create humanity.”

Despite the prescription of the death penalty in the Torah, it has always seemed to me that rabbinic discussions of capital punishment seek not only to limit but eliminate the practice of actually carrying out executions. The Mishnah’s statement attributed to Rabbi Elazar ben Azariah (Makkot 1:11), that a beit din who executes a criminal once every 70 years is considered a violent beit din suggests as much, as does the Mishnah Sanhedrin 4:1 and the gemara that follows which lays out the nearly impossible standards of evidence needed to convict.

Taking us far deeper into the complexities of rabbinic sources on capital punishment, our teacher Dr. Devora Steinmetz has written her book, Punishment and Freedom: The Rabbinic Construction of Rabbinic Law, to make the argument that the Mishnah and Talmud expounded the laws of execution not to deal with actual cases of murder and punishment (they didn’t even have the power to do so), but to express foundational ideas about human society and responsibility. I have also long been aware of, but have yet to read, the book Execution and Invention, by Dr. Beth Berkowitz, who is a professor of Talmud at Barnard.

I also recommend this CJLS Teshuva by Rabbi Jeremy Kalmanofsky on Onesh Mavet.

To these thorough and scholarly analyses I would add a reading, albeit an interpretative and perhaps expansive one, of the rationale of the Mishnah (Sanh. 4:1) that also appears in a related discussion in Bava Kamma 84A:“mishpat echad lachem, mishpat echad l’chulchem.” With this conditional phrase, the Talmud, I believe, insists that if capital punishment is to occur, it must be applied equally, meaning in a social context in which everyone has equal access to justice. That is demonstrably not the case in our society.

Recently, I spoke with a longtime friend who lives in Pittsburgh and is active in the Jewish community. He shared with me that as the trial was taking place, people he knew were vicariously reliving the trauma of 2018. I didn’t ask him what he thought of the likelihood that the death penalty would be handed down or his opinion on the matter. We didn’t get there in our conversation. I imagine that we would see things similarly, but without hearing from him I have no way of knowing.

I would like to think that he would join me in my interpretation of Jewish sources as idealized and theoretical rather than prescriptive. I also know that expecting as much from someone so close to the unimaginable experience is a tall order. And yet, isn’t that what we are supposed to do as rabbis and teachers, to challenge ourselves, as well as others, with all due compassion and empathy, so as to restore a measure of justice and healing to our world and try to preserve a cosmic balance?

Wishing you meaningful connections, work and the discoveries that emerge through them.

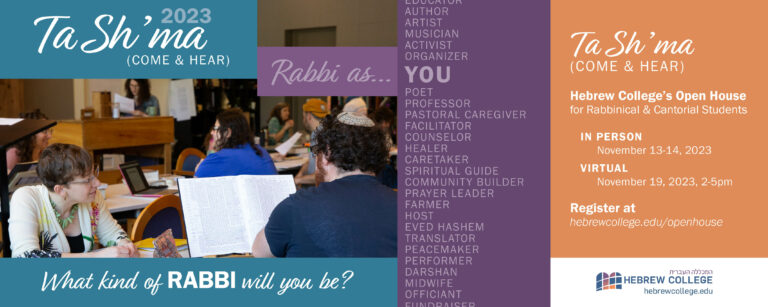

Learn more about Hebrew College’s rabbinical and cantorial programs at Ta Sh’ma (Come & Hear), our November Open Houses (in-person & virtual options).