Jewish learning Hebrew College Centennial Through an Archaeological Lens

Some Hebrew College graduates use their MAJS to DIG INTO Hebrew texts; Frankie Snyder used her MAJS to DIG UP a Hebrew text—literally.

Frankie graduated from Hebrew College in 2000, then worked in the Hebrew College library until 2003, when she became the administrator for the newly inaugurated Rabbinical School. In 2007 she made aliyah. Once in Israel, with a BS in mathematics and an MS in Jewish Studies, Frankie quickly found a niche archaeological career analyzing geometrically-shaped floor tiles, first on the Temple Mount (see “What the Temple Mount Floor Looked Like,” Biblical Archaeology Review Nov/Dec 2016: 56-59), then in several of King Herod’s palaces (see “Proof Positive: How We Used Math to Find Herod’s Palace at Banias,” in Biblical Archaeology Review Spring 2022: 52-58). But the best was yet to be discovered. (Pictured above: Frankie holding a floor pattern module containing some of the actual 2000-year-old tiles from the Second Temple complex floors)

In December 2019, Frankie was working with the Associates for Biblical Research (ABR), an international group of Christian archaeologists, who were in Samaria analyzing material from previous archaeological excavations on Mount Ebal. In the 1980s, Israel archaeologist Adam Zertal discovered what he believed to be “Joshua’s Altar” on Mount Ebal (Joshua 8:30-35). Mount Ebal is regarded as “the mountain of curses” while the adjacent Mount Gerizim is called “the mountain of blessings,” based on the covenant ratification ceremony held there when the Israelites first entered into the Promised Land (Deut 27:1-28:68).

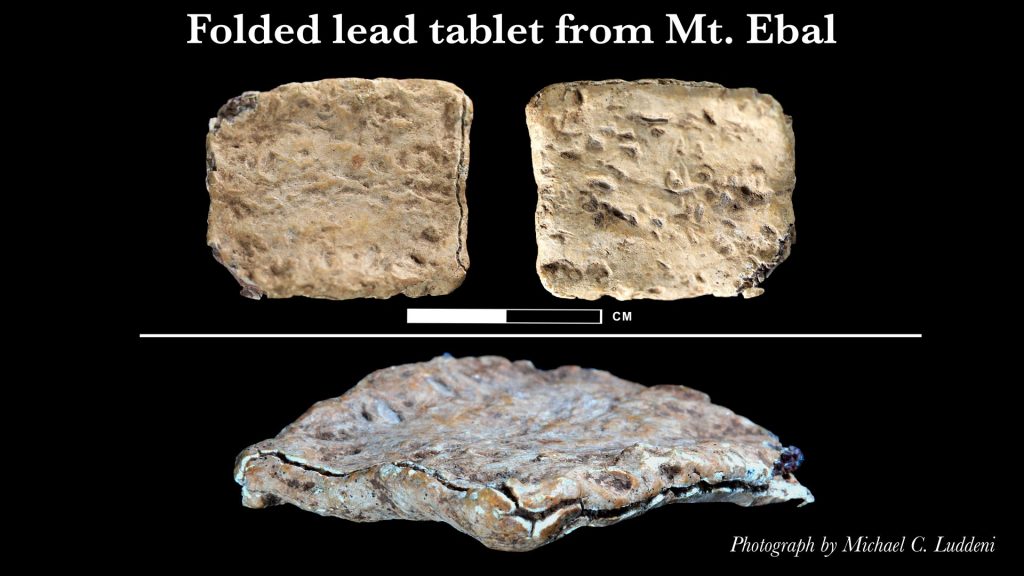

Material from Zertal’s dump of dirt and stones previously excavated and discarded from the interior of the altar were transported to a nearby moshav where the ABR volunteers meticulously searched for artifacts that Zertal’s staff may have missed many years before. Using a “wet-sifting” process where the material was studied after being washed off with a garden hose, Frankie suddenly saw something on her sifting tray. It was a small flat object, less than 1 inch square, that had once been a thin rectangular sheet of lead, now neatly folded in half. She immediately recognized it as a lead tablet, probably a defixio, a “curse tablet.” Her supervising archaeologist, Dr. Scott Stripling, was amazed at the find: a “curse tablet” from “the mountain of curses.”

Folded 3200-to-3400-year-old lead tablet from Mount Ebal:

front, back, and edgewise

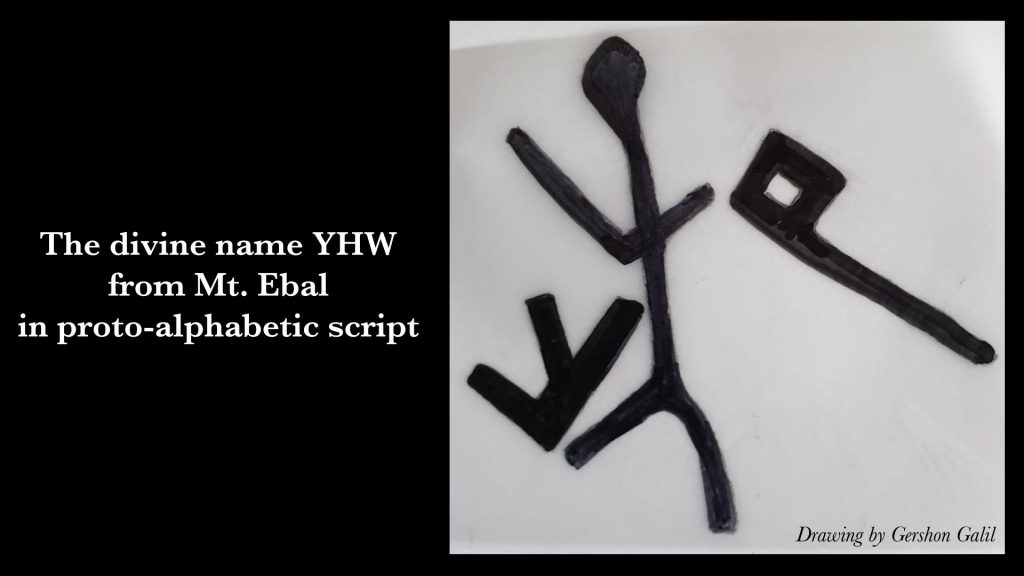

Since attempting to open the tablet would certainly destroy it, the tablet was sent to the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic Institute in Prague, where advanced high-tech tomographic scanning was employed to recover the inscribed text hidden on the interior the tablet while it was still folded. The results were astounding. The scans revealed 40 letters in a Hebrew script more ancient than proto-Hebrew, and the inscription has proved to be centuries older than any known Hebrew inscription from ancient Israel. Epigraphers from the Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz in Germany and the University of Haifa in Israel deciphered the proto-alphabetic inscription which follows a formulaic literary structure referred to written as “chiastic parallelism,” and reads as follows:

Cursed, cursed, cursed – cursed by the God YHW.

You will die cursed.

Cursed you will surely die.

Cursed by YHW – cursed, cursed, cursed.

The word “cursed” appears ten times in the inscription, but the most astounding thing is that the ancient Israelite divine name YHW appears twice.

Divine name YHW as it appears twice on the tablet

Divine name YHW as it appears twice on the tablet

Lettering on the exterior of the tablet, discovered in the tomographic scanning, is still being analyzed.

The tablet appears to be a legal document where an individual or group bound him/her/themselves to a covenant by inscribing and sealing the tablet, then placing it on the altar. Based on the specific Hebrew script, a chemical analysis of the lead in the tablet, and the pottery sherds which Zertal found at the site, the tablet has been dated to the Late Bronze II Age, c. 1400-1200 BCE, making this 3200-to-3400-year-old tablet the most ancient Hebrew inscription ever found in Israel.

Now that is really DIGGING UP a Hebrew text.