Numbers When the Earth Opened her Mouth

Parshat Korach, Numbers 16:1-18:32

The earth hath bubbles, as the water has, And these are of them. Whither are they vanish’d? (Macbeth, Act I;i)

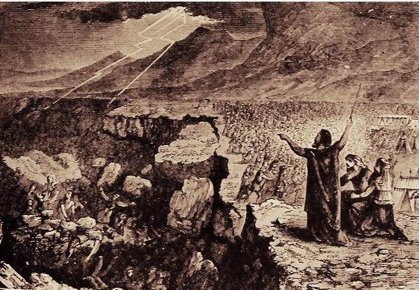

This week’s Torah reading features a complex rebellion against the leadership of Moses and Aaron—led, on the one hand, by Korah and a band a non-priestly Levites (16:3-7), and on the other, by the brothers Dathan and Abiram primarily against Moses and the whole Exodus project. The Rabbis hold this rebellion up as an example of “a dispute that is not for the sake of Heaven [machloket she’ayno leshem shamayim]” (Pirkei Avot 5:17). What is the difference between a dispute for Heaven’s sake (as in the machloket between Hillel and Shamai)—and a dispute that is not? The Mishnah goes on to explain that the difference lies in their endurance; the debate for Heaven’s sake persists while the other is subject to oblivion. Yet do we not read the story of Korah every year? It is part of the biblical canon! The fate of Dathan and Abiram—swallowed by the mouth of the earth—gestures at what is meant by “its end will not endure [ayn sofa lehitkayem]”.

The claims of the two rebels are rife with irony. The diagnostic test of the opening of the earth’s mouth serves as a punishment meted out, measure-for-measure, for their outrageous use of language. Moses summons them but they respond: “We will not come up [l’o na‘aleh]! Is it too little that you have brought us up [he‘elitanu] from a land flowing with milk and honey to kill us in the wilderness, that you must also lord it over us? Not only have you not brought us into a land flowing with milk and honey, or given us an inheritance of fields and vineyards, but you would gouge out the eyes of these men!?! We will not come up [l’o na‘aleh]!” (Num. 16:12b-14).

The rhetorical flourish in their refusal – “We will not come up [l’o na‘aleh]” which frames their speech – may refer to an elevated place, perhaps the Tent of Meeting outside the camp where Moses situates himself. Alternatively, they are expressing a vehement impiety, refusing to be subject to the figurative ascent towards God’s house or to the judgment of Moses who holds the higher moral ground. But the image of vertical ascent also resonates with their rejection of the project of ‘going up’ towards the Promised Land (‘aliyah), which they accuse Moses of failing to fulfill (v. 14). According to divine decree, in response to the debacle of the spies, this generation is doomed to die in the desert—“In this very wilderness shall [their] carcasses fall” (Num. 14:29). With their eyes figuratively gouged out, they will never see the “land flowing with milk and honey” – an epithet here Dathan and Abiram ironically attribute to Egypt. But as Rashi pithily notes (on v. 12), they damn themselves by their own words; in refusing to go up, they have nowhere else to go but down.

One might read Dathan and Abiram as the last representatives of the spies, who believed that Egypt and even the Wilderness were better than the true “Land flowing with milk and honey”. In their torpor of anxiety, the spies spread calumnies [dibah] about the land, claiming that it was “a land that consumes its inhabitants” (13:32). While the spies, whom Dathan and Abiram join ideologically, feared the Land of Israel devoured its inhabitants, they themselves are devoured by the desert.

Moses then sets up an audacious test, a supernatural intervention. Addressing Dathan and Abiram as they stand at the entrance of their tents, he orders the congregation to distance themselves from the perpetrators:

By this you shall know that it was the LORD who sent me to do all these things; that they are not of my own devising: if these men die as all men do, if their lot be the common fate of all mankind, it was not the LORD who sent me. But if the LORD creates something new [’im beri’ah yivr’a], so that the ground burst opens its mouth [u’fatztah ha’adamah piha] and swallows them up with all that belongs to them, and they go down alive into Sheol, you shall know that these men have spurned the LORD. (Num. 16:29-30).

Moses calls for a miracle, a new creation [beri’ah]—we have not seen this root [br’] since the Six Days of Creation (Genesis 1). According to midrash, this “mouth of the earth [pi ha-‘aretz]” was not new at all, but is among one of the ten things created at Twilight on the Sixth Day of Creation (M. Avot 5:6). It has been waiting since Primordial Time to open up its maw to swallow the rebels in order to undermine their claim and testify to Moses’ divinely ordained leadership. But why is the earth the site punishment? A natural death, “to die as all men do”, would entail burial in the earth [adamah], from which ha-Adam was taken, “for dust your are and to dust you must return” (Gen. 3:19)—and at a gravesite, memory endures. But here the earth splits asunder and swallows them and all their possessions, and “the earth closed over them and they vanished from the midst of the congregation” (Num. 16:33).

Throughout the Tanakh, the ground is personified as having a mouth that cries out, or swallows, or vomits up the casualties of human tragedy. The earth opened her mouth to swallow the blood of Abel, bearing witness to the original fratricide; from that cursed ground Cain is exiled, condemned to wander the world as a fugitive (Gen. 4:10-11). In his poignant cris de coeur, Job calls for the earth not to cover his blood or silence his cries so that the injustice of his suffering might ascend to Heaven (Job 16:18). Further, the violation of God’s Laws concerned with holiness would contaminate the Land and force it to vomit the people out (Lev. 18:28, 20:22). But now those who rejected the whole Exodus project are swallowed alive. In refusing to test the ground (so to speak) of ‘aliyah to the Promised Land, they go down, down, down, to Sheol, to “the undiscovered country from whose bourn no traveler returns.” No bodies to mourn. No testimonial to natural death. No grave to mark their passing. The face of the earth returns, seamlessly, to its mute state as if never rent asunder. Unlike other sinkholes in the earth, this “mouth of the earth” swallowed the combatants and closed up again, leaving no trace.

This is the destiny of claims that are “not for the sake of heaven [macholoket she’ayno leshem shamayim],” where language has no compass of truth—no orientation of above and below, of forward and backward in either time of space. Pirkei Avot avers that such a debate will not endure—“ayn sofa lehitkayem”—though the haunting story of the claimants’ fate persists.

Explore Hebrew College’s Rabbinical Ordination Program

Dr. Rachel Adelman (PhD Hebrew University of Jerusalem), is Associate Professor of Bible at the Rabbinical School of Hebrew College, Newton, MA

[1]Outside of this context, the expression “a land flowing with milk and honey אֶרֶץ זָבַת חָלָב וּדְבַשׁ “ is used exclusively with respect to Land of Israel: Exod. 3:8,17; 13:5 and 33:3; Lev. 20:4, Deut. 6:3, 11:9, 26:9,15 and 27:3. Josh 5:6, Jer. 11:5, 33:22.

[1] This idea was inspired by an essay by Yonatan Grossman, “The Symbolic Significance of the Earth ‘Opening her Mouth’”, https://www.etzion.org.il/en/symbolic-significance-earth-opening-her-mouth.