Community Blog Hebrew College Pilgrimage to Ukraine

For nearly 60 years, Hebrew College Rector Rabbi Arthur Green has been studying the writings of the Hasidic masters, spiritual revivalists and mystics who lived and wrote in Ukraine during the 18th Century — creating a movement that emphasized the ability for all Jews to grow closer to God by noticing the divine presence everywhere, seeking the magnificent within everyday life, and doing all things with love and joy.

Rabbi Green, who started the Rabbinical School at Hebrew College, is recognized as one of the founders and leading scholars of the neo-Hasidic movement, applying the spiritual insights of the Hasidic masters to contemporary egalitarian Judaism as practiced by those who do not live within the strictly-bounded religiously conservative world of the modern-day Ultra-Orthodox Hasidic community.

And this summer, for the first time, Rabbi Green traveled to Ukraine to visit the graves of the Baal Shem Tov, or “Master of the Good Name,” the founding father of Hasidism, and his disciples. He brought with him nine students and friends, including Hebrew College professors Rabbi Ebn Leader, Rabbi Allan Lehmann, and Rabbi Jordan Schuster, Rab`18, and Hebrew College alumni Rabbi Lee Moore, Rab`10, Rabbi Getzel Davis, Rab`13, and Rabbi Elie Lehmann, Rab`17; as well as Ariel Mayse, a former PhD student of his and professor of religious studies at Stanford; Rabbi Avram Mlotek, co-founder of Base Hillel; and Reb Mimi Feigelson, spiritual mentor of the Schechter Rabbinical Seminary.

“You would call it a spiritual pilgrimage to see the places where Hasidism originated, to visit the graves of Hasidism’s early leaders, to get a sense of what the atmosphere was like,” Rabbi Green said. “These were mythical places for me. When I started studying this field in the early 1970s, this was all behind the Iron Curtain. You couldn’t go there. And the Holocaust memory was very alive. So this was a very moving and powerful experience.”

The trip preceded a conference on the history of Hasidim sponsored by Hebrew College, Bar-Ilan University, Brandeis University, and several other institutions, which drew Rabbi Green to the region. His former student, Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, professor of Jewish Studies and History at Northwestern University, who grew up in Kyiv, offered to plan the excursion.

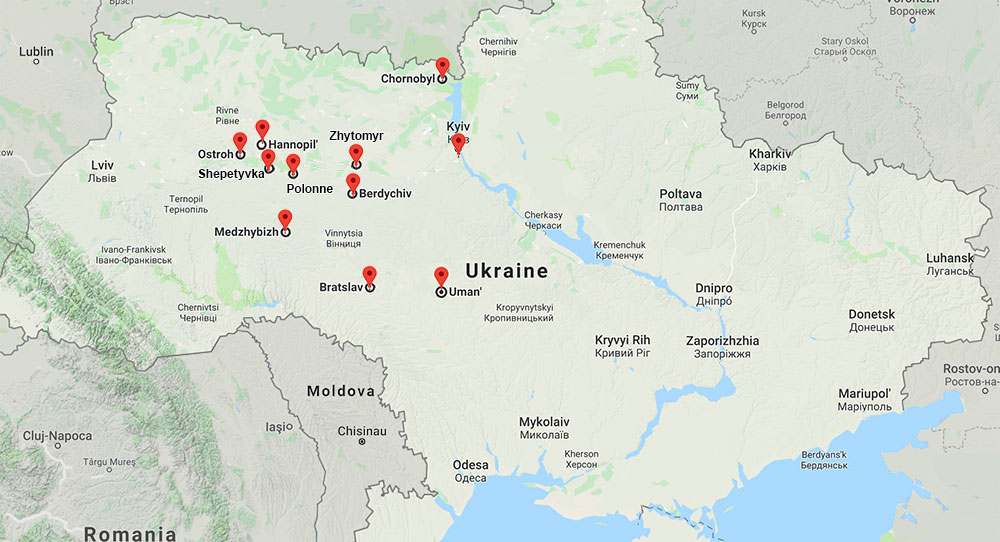

The group toured former synagogues, cemeteries, and prayer sites in Kyiv, Chernobyl, Uman, and elsewhere, and saw the grave sites of numerous Hasidic leaders, including The Baal Shem Tov, a spiritual teacher and shaman known to spend long stretches of time meditating and wandering in the woods; his successor, The Maggid of Mezritch, who published one of the first works of Hasidic thought; R. Menahem Nahum of Chernobyl, a disciple of the Baal Shem Tov; and Rebbe Nachman of Braslav, a great-grandson of the Baal Shem Tov.

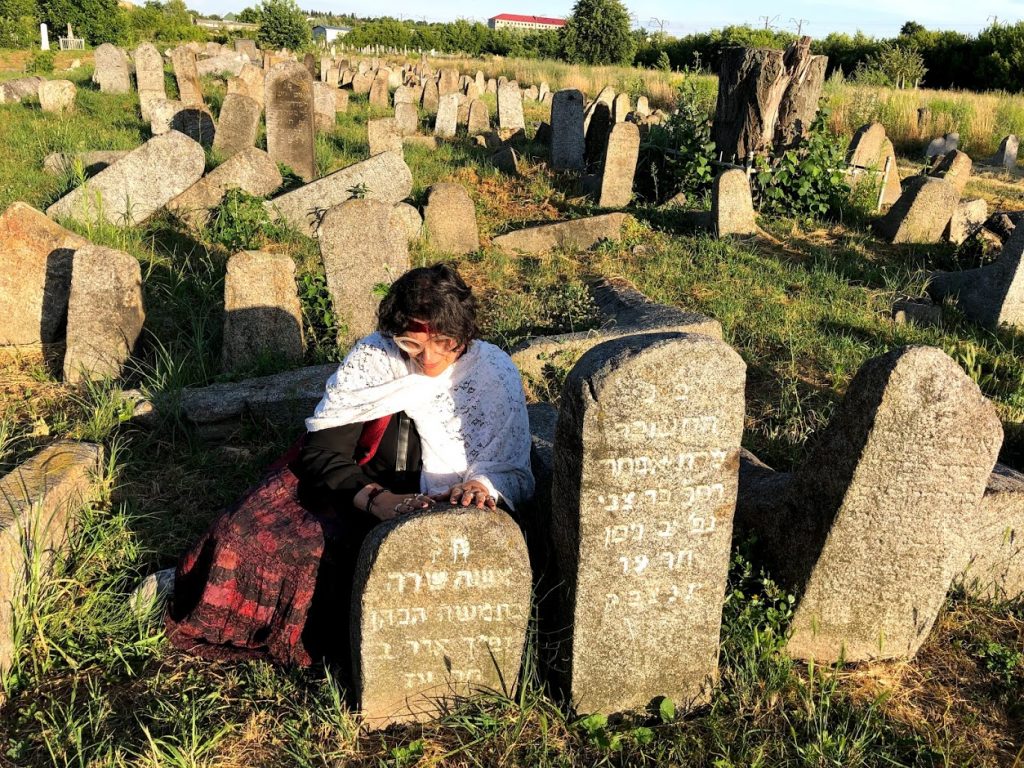

And while other religious pilgrims — including Ultra-Orthodox Israelis and North African Jews — were praying at the graves and memorials for the rebbes to intercede with God to help with problems in their lives, Rabbi Green’s group was on a different kind of pilgrimage — reading and singing the writings of the rebbes and discussing their meaning within the modern frameworks of progressive politics, pluralism, and egalitarianism; praying and meditating at the rebbe’s graves; and posting reflections and videos on social media.

“We all went with such different motivations, backgrounds, and interpretations of what these rebbes were saying, and with such different relationships to gender and how that informs the ways that we were reading, interpreting and teaching the rebbes,” Rabbi Schuster said. “I think it felt really big for all of us in very different ways.”

“I think the meta question of the journey was: Can liberal Jews do religious pilgrimage as liberal Jews?” Rabbi Leader added. “I think we succeeded, but it is not simple.”

Because the rebbes lived in a world of gender separation, the men and women in the group were often required to separate. At Rabbi Nachman’s grave, they tried to walk into the men’s side together and were stopped by a guard. At the grave of The Maggid of Mezritch, where they were the only pilgrims present, they disregarded the gendered signs and occupied both the men’s and women’s spaces. At the grave of Levi Yitzchak of Berdichev, they found a group of 60 women on a Rosh Chodesh trip from Israel.

“The women were passionately crying out their prayers over the grave. The women from our group joined them and the men tried to respect their prayer space by huddling behind a mechitzah,” Rabbi Davis chronicled on Facebook. “We men had the rare growth opportunity to both experience a prayer space designed to exclude us and to witness a traditional expression of Jewish female prayer that usually doesn’t happen anywhere near progressive men. After the group left, the whole tziun felt like it was vibrating with the rebbe’s energy. It’s now five hours since we left and am only now coming down from the ecstatic prayerful attunement. I feel charged and recharged.”

And at each grave, the group responded differently. At the grave of the Kedushat Levi, Levi Yitzchok of Berditchev, they sang for nearly 30 minutes, sometimes softly, sometimes with heightened fervor. At the grave of The Maggid of Mezritch, a placid location overlooking a river, several members of the group sat in total silence.

“The mythic promise of pilgrimage is that there’s power at these sites that you’re going to tap into — that something of the Rebbe’s presence remains there and is going to transform you,” Rabbi Schuster said. “Where does that power come from? The imagination? The group that you’re with that’s sharing stories about them? I feel like I’m communing with the rebbes when I read their texts. And it definitely felt like that when I was there.”

Rabbi Davis, who had visited the region twice previously, brought with him 15 prayers from friends and family for the rebbes. He also left a gift by the grave of Rabbi Nachman — an egalitarian prayer book — in hopes of inspiring a world where “not only can us egalitarians continue to learn deeply from his wisdom, but that his spirit too can grow to integrate the truths of feminism and xenophilia,” he posted, along with the hashtag #EgalUman.

“I found it really powerful to commune or daven or have spiritual experience in the vicinity of these rebbes. Every stop along the way had very different energy, and felt like each of the rebbes had different wisdom to share. It really felt like having an audience with a lot of them,” Rabbi Davis said. “We cried, we danced, we learned, and there was a lot of awareness and processing around gender.”

The group was also affected as they encountered the more recent history of the Holocaust, including sites where tens of thousands of Jews were killed. Davis recalled that during their visit to Babi Yar, where 33,771 Jews were murdered in two days in 1941, Reb Mimi Feigelson suggested that the group recite Kaddish and leave long pauses to allow those who died to respond. He said he felt like he needed to go to a mikvah afterwards to cleanse the energy after the experience.

The group was also moved by the experience at the grave of Menachem Nachem of Chernobyl, close to where the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant disaster took place in April 1986. It took them three hours on a specially-equipped bus and documented permission from the Ukrainian government to visit the site. The group’s tour guide had never before led a group that just wanted to visit the gravesite and not Pripyat, the area most affected by the explosion.

“His tziun (gravesite/house) is only a locked little brick building with his grave in the middle covered with kvitlach (handwritten petitions). There was just enough room and light inside for the 11 of us to hold hands and dance in a circle,” Rabbi Davis wrote on Facebook. “Friends, I don’t really know how to describe it, but the cramped dark room seemed so filled with the rebbe’s warm and constant love-light. Manachem Nachem is the author of the Meor Enayim, a hasidic text that insists over and over that everything and everyone one is nothing but G!d. It was bizarre to encounter this rebbe’s simple love while visiting a place known for its destruction.”

Rabbi Moore said seeing the towns in “technicolor” — rather than black-and-white photographs — brought the rebbe’s stories to life. As they passed the landscape on the bus, they shared texts, stories, and nigguns to prepare for their next stop.

“One Jewish way of talking about God is the term makom, which means ‘place.’ It’s such a powerful way of thinking about God because it’s beyond gender, even beyond thinking of God as a person,” she added. “During this pilgrimage, makom was not only the places where we were visiting, but also the kind of space that we created as a group visiting together. To me, makom was a theme — the geographic place where my ancestors were from, experiencing holiness in these places where the rebbes lived, and the added layer that place is created by people in their wanderings, by us as a group.”

At the end of the trip, during a Shabbat meal in Uman, Rabbi Moore suggested that the group have a conversation about the future of neo-Hasidism. The conversation touched on the legacy of the rebbes, the contemporary Hasidic movement, and what spiritual seekers are looking for today.

“I felt called to go on this trip — this opportunity to forge a more direct connection with the Hasidic masters, not only through their writing, but also through the places where they lived — that felt huge to me,” she said. “To me, it’s very special that a group of rabbis such as us undertook this kind of pilgrimage. It’s not just that we’re a group of liberal rabbis. We’re a group of liberal rabbis who nevertheless see our roots in the traditions that came from these masters. For myself, part of what that means is going back to the basics, to a Judaism that is accessible in its teachings for leading a good life, for finding joy even in really difficult times, for understanding that the inner psychological workings of our lives are where our spirituality plays out. When I feel proud to say that I’m neo-Hasidic, that’s a large part of what I mean.”

Rabbi Green said he has been meaning to visit the graves of the Hasidic masters since the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, but never found the right opportunity. He was moved by the experience — by seeing the towns as they have been for centuries, with thatched roofs, vegetable gardens, vast fields of wheat and sunflowers, and chickens and goats running through the bumpy streets, and by the graves that have been cleaned up by Hasidic pilgrims from Israel. He hopes to return on another pilgrimage in the near future with a larger group of Hebrew College students, alumni and friends.

“A pilgrimage is about breaking out of the boundaries of your life to go explore and search for some sort of meaning that has been eluding you — to do this with other people who are on a similar quest,” Rabbi Schuster said. “It’s a really powerful framework to exist in, and one that was so central to biblical Judaism, so central to Rabbinic Judaism before the destruction of the Temple, and so central to Hasidic Judaism after these graves were first erected. It was fascinating to make this kind of pilgrimage with Art and a group of neo-Hasids. I went for it — I stepped into the framework — and I am coming back different.”