Interreligious Learning and Theology

-

This unit wants you to ask

-

By the end of this unit you will…

-

The resources in this unit include…

- How can we learn from and pursue theological questions with people from other religions?

- How does my worldview shape my interreligious work?

- How can one approach a text, idea, or story shared across multiple traditions in a group setting with members of other traditions?

- Be able to identify overgeneralizing statements about religious traditions.

- Know how make sense of and describe how your own worldview shapes your interreligious work.

- Begin reflecting on and comparing the similarities between interreligious leadership and democracy.

- A quote from sociologist Jonathan Z. Smith

- “Never Wholly Other” by Jerusha T. Lamptey

- “Confucian Wisdom and Interreligious Dialogue” by Yan Wang

- Comparative art from Jewish, Muslim, and Christian traditions

Is it possible that religious traditions make good sense of religious diversity so that they are in a position to learn from each other or even to pursue their own kind of theological questions together with people from other religions?

Watch the full video here.

Dr. Perry Schmidt Leukel, Professorship of Religious Studies and Inter-Faith Theology

This unit seeks to bring about more questions than answers. The goal is for learners to become more comfortable asking the question posed by Dr. Perry Schhmidt Leukel and others like it in interreligious spaces: how can we learn from and pursue theological questions with people from other religions? Is it possible to have constructive interchanges while navigating our different views of theological sources for example? What can we learn about our own worldviews or theologies through these exchanges?

No Data in Religion

Sociologist Jonathan Z. Smith famously stated, “while there is a staggering amount of data, phenomena, of human experiences and expressions that might be characterized in one culture or another, by one criterion or another, as religion—there is no data for religion.” If you have ever felt discomfort upon seeing something online along the lines of “Judaism says X” or “Hinduism says Y,” then you understand what Smith is referring to. Specific religious traditions (which do not always have distinct and clear lines) do not “speak” or have opinions. Individuals who identify with various traditions—including scholars, communal leaders, and lay followers—say, interpret, and have opinions on things. After all, it’s impossible for abstract ideas like “Judaism” or “Shintoism” to talk!

Equipped with Smith’s quote, think about conceptions of your faith. Write six statements you commonly hear about your own religion. Which statements resonate with your experience of your tradition? Which statements feel alien to your experience? In what way do these commonly held ideas shape the way that others perceive your tradition?

Self-Reflection and Theology

It’s very easy to forget how our own traditions shape, nourish, and occasionally direct our interreligious lives. In her article “Never Wholly Other,” Jerusha T. Lamptey writes:

The embrace of interreligious engagement – that is, the practical embrace of the religious ‘other’ – has not necessarily been paired with a theological embrace of the religious ‘other.’ In fact, there frequently exists a gap between practical action and theological understandings of religious ‘others.’ … Bifurcation between the practical and theological is problematic because the two topics are treated as if they do not come into contact, nor inform one another.

Lamptey provides an example, from her own religious tradition, of some Muslims who “are fully committed to interreligious engagement and detest interreligious strife, yet still harbor theological commitments to the finality, uniqueness and superiority of the religion of Islam.” While Lamptey speaks about members of her own religious community, examples of such contradictions between theology and practice can be found across the religious landscape.

The intention to be in honest dialogue with others whose faith and belief commitments do not mirror one’s own is a holy endeavor and one that is challenging to fulfill. How can we be loyal to deeply felt beliefs, core values, faith experiences and simultaneously listen with compassion, intellectual openness, and curiosity to other voices which highlight “otherness” in belief and faith practices?

How does your own tradition influence your interreligious work? Think back to Unit 1 and the Big 8. How might your “Big 8” be relevant to your interreligious actions? In what ways do your identities limit perspectives of the other?

Guiding Questions:

-

- What “single stories” do I hold about interreligious cooperation and solidarity work?

- What social and/or political issues am I passionate about? Does my own religious background and experience influence my outlook on these issues?

- Write down the first 5-10 words that come to mind when you hear the phrase “interreligious work and advocacy.”

- Do the words reflect your own social / religious experiences? What words might someone from a different background be surprised to find left off your list?

Group Activity: Making Sense of Worldviews, Together

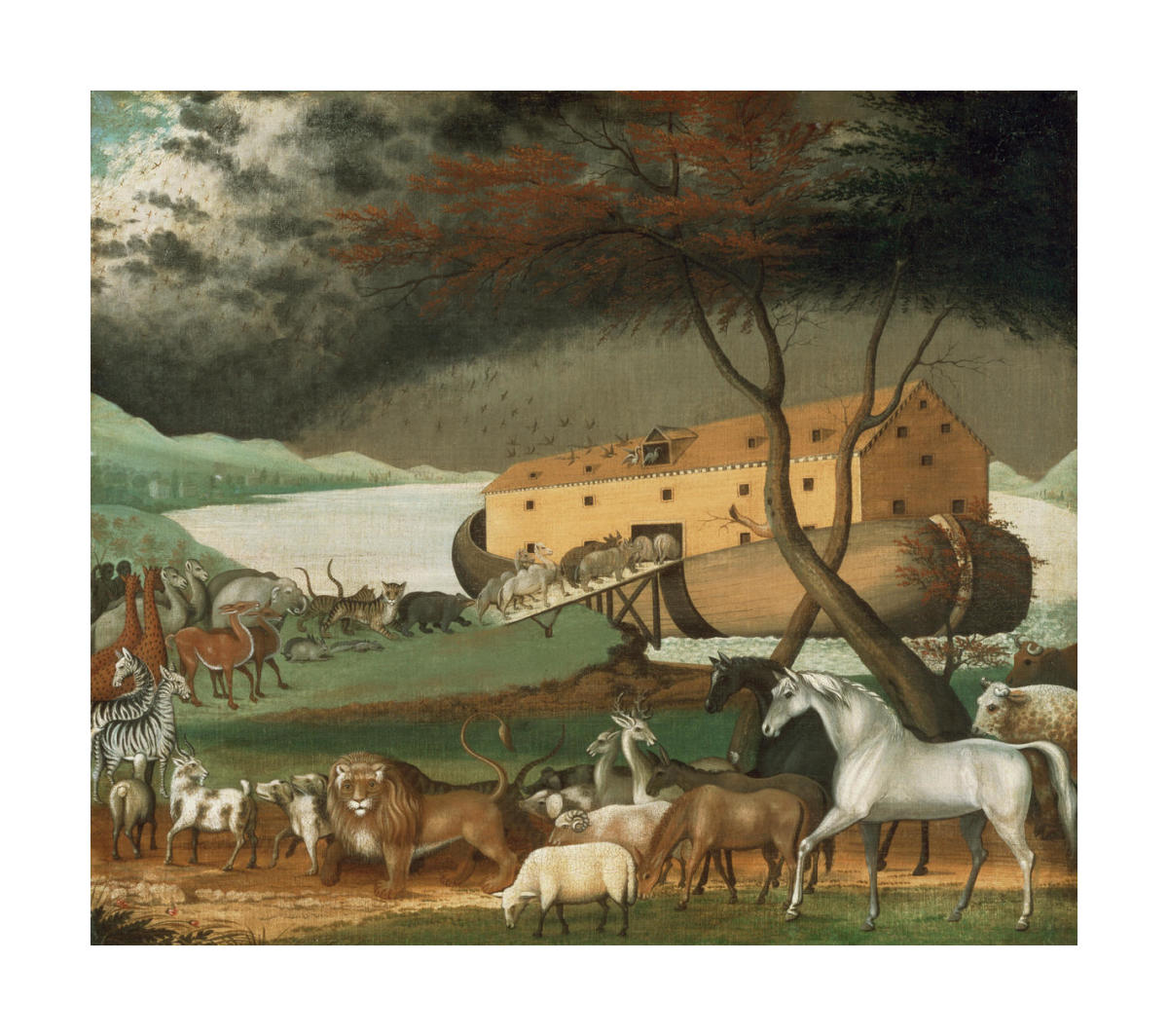

We have already examined the limitations and challenges to learning together in interreligious groups. Now let’s consider the value and meaning that can be generated through interreligious study groups. One way to do this is to study a text, story, or image shared by multiple traditions. For example, the overarching religious and cultural narratives related to Noah’s Ark acquire their own flavor in each of the Abrahamic traditions. If you’re only familiar with the biblical account, read the Quranic account—and vice versa if you’re only familiar with the Quranic one. If you’re not familiar with either or if it’s been a while, you might want to read both versions.

In small groups of three or four, reflect together on the following images of the famous biblical and Quranic story of Noah’s Ark.

Confucian Wisdom and Interreligious Dialogue

One of the most beautiful things about interreligious dialogue and learning is the field’s rich depth of potential sources for wisdom. Thinkers from so many different religious traditions and worldviews frequently share insights from their own spiritual contexts and experiences with the broader world of interreligious dialogue and other peacebuilding initiatives. For example, in his blog “Confucian Wisdom and Interreligious Dialogue,” Yan Wang, a Christian minister and former professor of Judaic Studies at Shandong University, China, points to a teaching from the Analects as potentially useful in interreligious settings:

In Analects [the Sayings of Confucius], Confucius says, “A gentleman aims at harmony, and not at uniformity.” I believe that the Confucian notion of seeking harmony, not an abstract truth, can help different religious traditions coexist peacefully in spite of their conflicting truth claims. The Confucian way of thinking is relational. In the Confucian understanding, a person’s existence and its meaning and value can only be found in one’s relations within one’s family, community, and the nation at large…

Confucian wisdom also provides advice for how to conduct interreligious dialogue. To seek common ground while maintaining differences, Confucianism emphasizes, shall be the guiding principle in our social interaction.

What sources, insights, or scriptures from your own religious traditions and worldviews do you think have the potential to contribute to the success of interreligious dialogue? How could you use these sources? What sources, quotes, or stories first come to your mind?

Group Exercise: Crime Solving Activity

Each member of your group will receive a piece of paper (or multiple) with information pertaining to a crime. The object of the activity is to solve the investigation of a crime with the information at hand.

Some of the information will be shared information, which is common to multiple or all members. However, some of the information will be unshared information, or information that is unique to particular members before discussion of the information. Leveraging communication skills, leadership, and interpersonal relationships, try to arrive at a unanimous opinion on who committed the crime. Before discussing information as a group, write which of the three suspects you think committed the crime based on the information in the “basic situation” and on your own information. The activity should be printed and disseminated. The answer is available here—do not look until the activity’s conclusion!

After finishing the activity, you may or may not be clueless as to what it has to do with interreligious theology! When we do theology together with people of faiths other than our own, after all, we are unlikely to arrive at the “right” answer together. Maybe there isn’t even a single, right answer! For this activity, the “answer” is made-up—as is the entire activity. It’s possible to come up with brief explanations for how the other two suspects committed the crime rather than the person we said did.

But the answer is not entirely irrelevant. How did your group get to the answer? Did one person facilitate the conversation? What happened when there were disagreements? How were problems solved? What was the shared “goal” of those playing and how might that be relevant to the types of discussions we have been having? Perhaps most importantly, what skills could this activity help refine?

These questions may help direct conversation in a fruitful manner to the activity’s relevance to interfaith theology.

Want to Learn More?

- Words to Live by: Sacred Sources for Interreligious Engagement, edited by Or N. Rose, Homayra Ziad, & Soren M. Hessler.

- “Paganism and Interfaith in the UK and Europe” by Mike Stygal in The Interfaith Observer

- Stephen Prothero: God Is Not One (Video)