Deuteronomy Who are We to Judge?

Parashat Shoftim Deuteronomy 16.8-21.9

Parshat Shoftim is aptly placed at the beginning of Elul. It opens with the following instruction:

שֹׁפְטִ֣ים וְשֹֽׁטְרִ֗ים תִּֽתֶּן־לְךָ֙ בְּכָל־שְׁעָרֶ֔יךָ אֲשֶׁ֨ר יְהֹוָ֧ה אֱלֹהֶ֛יךָ נֹתֵ֥ן לְךָ֖ לִשְׁבָטֶ֑יךָ וְשָׁפְט֥וּ אֶת־הָעָ֖ם מִשְׁפַּט־צֶֽדֶק׃

לֹא־תַטֶּ֣ה מִשְׁפָּ֔ט לֹ֥א תַכִּ֖יר פָּנִ֑ים וְלֹא־תִקַּ֣ח שֹׁ֔חַד כִּ֣י הַשֹּׁ֗חַד יְעַוֵּר֙ עֵינֵ֣י חֲכָמִ֔ים וִֽיסַלֵּ֖ף דִּבְרֵ֥י צַדִּיקִֽם׃

צֶ֥דֶק צֶ֖דֶק תִּרְדֹּ֑ף לְמַ֤עַן תִּֽחְיֶה֙ וְיָרַשְׁתָּ֣ אֶת־הָאָ֔רֶץ אֲשֶׁר־יְהֹוָ֥ה אֱלֹהֶ֖יךָ נֹתֵ֥ן לָֽךְ׃

(18) You shall appoint judges and officials for your tribes, in all the settlements that God, your God is giving you, and they shall govern the people with due justice. (19) You shall not judge unfairly: you shall show no partiality; you shall not take bribes, for bribes blind the eyes of the discerning and upset the plea of the just. (20) Justice, justice shall you pursue, that you may thrive and occupy the land that your God יהוה is giving you. -Deuteronomy 16:18-20

Here, at the beginning of the month of repentance, reflection, course correction—when we are tasked with judging our own actions for over the past year as we prepare to stand and be judged by the Holy Blessed One—the Torah stresses the importance of fair, unbiased judges. Being able to make judgements that rise above the pettiness of bribes, we learn, is of the utmost importance in building a society that is just and thriving.

Torah commentators clarify that the second verse—that we must not judge unfairly—means we must hold our understanding of the law no matter what individual is standing before us. Whether they are our brother or a stranger, a long-time community member or a new-comer. Even if they are palming us bills under the table or offering to make a sizable donation to our congregation—we must not let our relationships or money cloud our judgement.

A tall order. How, then, does one cultivate this disposition?

The rabbis of the Talmud offer an answer to this question in discussing what qualifies a judge to sit on the Sanhedrin—the highest court of 70 judges that rules on death penalty cases.

אמר רב יהודה אמר רב אין מושיבין בסנהדרין אלא מי שיודע לטהר את השרץ מה”ת

Rav Yehuda says that Rav says: They only place on the Sanhedrin one who knows how to render a creeping animal pure (le’taheir et ha’sheretz) from Torah law.

Sanhedrin 17a

A sheretz is the Talmud’s quintessential unkosher creepy crawler. It’s a bug and it’s not kosher. So, Rav says, to sit on the Sanhedrin and rule on life and death, you must be able to argue convincingly on behalf of the Torah’s grossest animal.

This makes sense: in order to be able to judge fairly, one must be able to look past everything else one might think or feel about a person, and instead look only at their actions and the impact of those actions on others. So, the rabbis say, practice this disposition by delving into the depths of Torah to argue that even a bug that the Torah explicitly says is the farthest from holiness—even they can be holy.

Rabbi Benay Lappe, in an article in 2003 advocating for the full inclusion of queer people in Jewish life, takes the value of this exercise one step further. She explains more fully just how important this quality is for the task of pursuing justice, set out so resolutely in Parshat Shoftim:

So what was the point of training rabbinic students with such analytic acumen and audacity that they could find a way to declare clean that which the Torah deemed unclean—something that was clearly “impossible”?

It was so that when an overly formalistic application of a Torah verse yielded an intolerably harsh or oppressive result for a class of people—in which suffering was in fact caused by the laws of the Torah rather than alleviated by them—our rabbis would have not only the skill but also the courage to utilize the tradition in radical yet authentically Jewish ways to relieve that suffering, even if it initially appeared “impossible” to do so.

A judge who can recognize suffering and find justification to end it, who can see past societal expectations or internalized aversions to advocate for the downtrodden, marginalized, and stigmatized—those are the judges we want at our gates.

Over the next few weeks, we will judge ourselves and seek teshuva—course correction, we will judge others and give tochecha—rebuke, and we will be judged by God, and seek mercy.

This year, may we seek, and may we be, judges like those of the Sanhedrin: aware that we bear a great responsibility, and may we strive to be compassionate and understanding towards even that which we find most abhorrent.

Rabbi Frankie Sandmel (they/them), Hebrew College Rabbinical School `22, runs Base Bay where, together with their partner Elaina, they are building a vibrant, rooted, and resonant Jewish community for young adults out of their home in Oakland. In their free time, Frankie is a fellow with SVARA: A Traditionally Radical Yeshiva and they bake a lot of cookies.

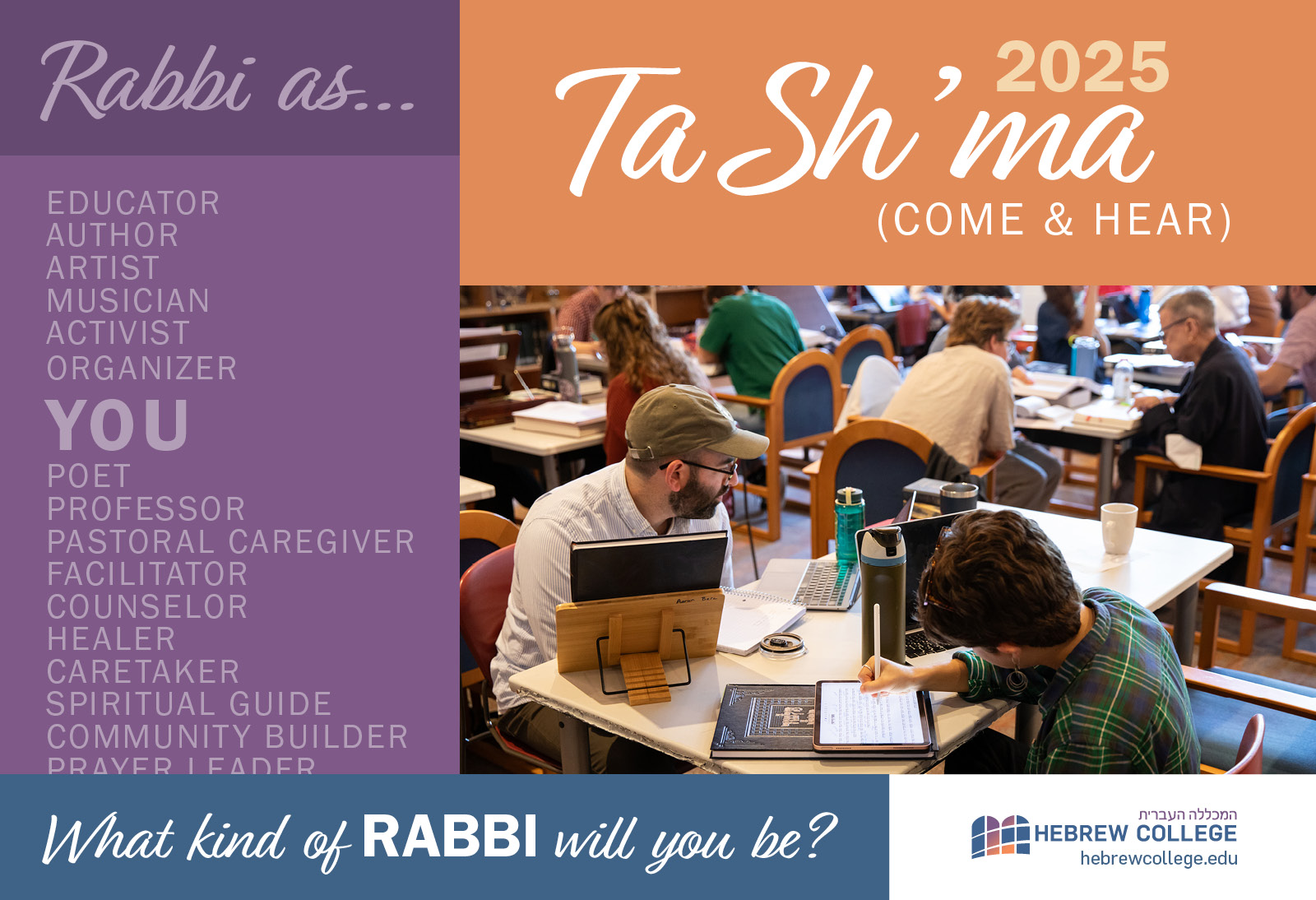

Meet students and faculty at one of our fall open houses, Ta Sh’ma (Come & Hear) November 18 (in-person) or online (Dec. 8). Learn more and register.