Community Blog The Torahs of Music

Joey Weisenberg is one of the most dynamic forces in Jewish music today. His warm spirit and his ability to help people come into the present moment with each other, with themselves, and with God through the practice of communal singing is a beautiful thing to watch. I fondly remember sitting together with him and a dozen other people — a motley crew united by their humble spirits and musical ears — in the choir loft of the Kane Street synagogue for Weisenberg’s first recording. He knew just how to guide us, how to help us unite as singers, to sit with silence, and to have our spirits swing together on the monkey bars of each sweet melody.

Eight years have since passed, and the Jewish world has seen the immense growth of this type of singing and musical community. Weisenberg has composed and produced almost a dozen recordings, published two books, and has launched Hadar’s Rising Song Institute – a Philadelphia-based “music yeshiva” dedicated to cultivating Jewish spiritual life through song. The movement of communal singing and its accompanying wisdom tradition are now uniquely taking root in expanding institutional forms.

“The Torah of Music” is a new handbook for this movement; it is an ode to the blessings of singing together, of music, and of the spiritual fruits it yields as reflected in the Jewish textual tradition. The first part of the book comprises ten chapters of “Studies and Stories,” each exploring the potential of music, dancing between Jewish religious texts, anecdotes, and reflections on music as a spiritual practice. Looking at these studies, one can see the priorities and values of Weisenberg’s musical philosophy. These include “Quieting (Chapter 3),” Listening (Chapter 4)”, “Joining Together Through Song (Chapter 5)”, “Songs of Struggle (Chapter 7),” and “Brokenness & Wholeness (Chapter 8).” These chapters, which weave together diverse Jewish texts with wisdom from Weisenberg’s extensive experience as a musician and prayer leader, all point to one of the book’s underlying ideas — that the practice of making music (particularly with others) teaches us deep truths about how to live a sensitive, spiritual life in community. Pointing to its power to release emotions, to reduce tensions, to bring unity, and to resensitize the soul, Weisenberg recognizes the human vitality lying behind a musically rich life. He emphasizes: Music signifies life…To sing is to be fully alive.”

The second part of the book is a beautifully curated collection of Jewish texts about music spanning from Torah to the 20th century. This is a unique and rich resource for cantors, prayer leaders, and Jewish musicians to study, as it elegantly strings together pearls of Jewish wisdom that show how music helps to evoke wonder, struggle, meaning, and personal growth. The book further models the unique depth of Weisenberg’s (and Hadar’s) approach to music as being grounded in a commitment to serious Jewish learning. Of special note are the incredibly evocative translations by Joshua Schwartz, whose linguistic artistry makes the words sing themselves off the page.

The Torah of Music shows Joey’s heart on his sleeve, as he encourages the reader to join in his vision of the transformative power of music. Nearly each chapter ends with a prophetic vision yet to be realized, a prayer for our musical future: “It should only be that Torah helps us sing our new ancient song!…Let us find our melodies, and let us find our prayers, and let us bring the world to life!” ….Can we allow our Amens to remind us of the songs that are sung by all of creation?…May it be that we sing every day as though it were our first time singing!” One senses Weisenberg’s own sensitivity here, feeling the divisions in the world and longing to heal them through the Torah and through the models of music-making and prayer that he so beautifully masters and teaches.

The title of the book itself bears noting as being “The Torah of Music” and, significantly, not “Music in the Torah.” Here Weisenberg recognizes that the human practice of music-making actually reveals its own inherent wisdom. As the preface puts plainly: “In this book, we’ll look not only at teachings from the Jewish tradition that involve music, but also at what music itself has to teach us.” Like the figure of Wisdom in the Book of Proverbs, or the Greek Muses on which the English word is based, “Music” stands alone as a personified self, filled with attainable insights of significant religious (or at least “spiritual”) value.

But who is this “Music” whose Torah we seek? Like “Judaism” and “Community,” “Music” is a word with seemingly monolithic and obvious meaning, and yet contains multitudes of intersecting and diverging human values and practices. To understand the enterprise of Joey Weisenberg and of this book, we must define the context and compass of this term.

The contemporary culture of Jewish communal singing — exquisitely championed by Weisenberg– is an outgrowth of our therapeutic age. This age was foreseen by Phillip Rieff, one of the first cataloguers of Freud’s papers (and also mentor to Dr. Arnold Eisen, the outgoing Chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary). In the wake of Freud, Rieff saw that our age was moving away from culturally-bound limits and beliefs towards the renewed idealization of feeling and expression. In envisioning the effect on culture, Rieff prophetically observed:

“In the emergent culture, a wider range of people will have “spiritual” concerns and engage in “spiritual” pursuits. There will be more singing and more listening… People will continue to genuflect and read the Bible, which has long achieved the status of great literature; but no prophet will denounce the rich attire or stop the dancing. There will be more theater, not less, and no Puritan will denounce the stage and draw its curtains. On the contrary, I expect that modern society will mount psychodramas far more frequently than its ancestors mounted miracle plays.”

Amidst a world which continues to see cultures as exclusive, discriminating, and violently limiting human possibility, the Hadar Institute (under which Weisenberg’s work is organized) boldly straddles the border of Conservative thought and modern-Orthodox practice, committed to expanding, but never eliminating, norms of Jewish practice and life. In my own estimation, it is because Hadar is so countercultural in this way that it concomitantly requires and cultivates a strong therapeutic music culture to sweeten the Torah and norms of Jewish practice that it so fiercely defends and develops. Weisenberg’s own language about music embodies the God-within, therapeutic enterprise, sweetening music-making for the average Jew and complimenting the work of other Hadar leaders: Rabbi Shai Held (who sweetens theology & Torah with a focus on kindness and love, which also forms the basis of his renewed prophetic critiques of society); Rabbi Ethan Tucker (who expands halakhic possibility while maintaining halakhically-bounded discourse); and Rabbi Elie Kaunfer (who sweetens the words of the prayer book, and also works on improving institutional and educational structures in American Judaism).

I would contend that The Torah of Music, is also, at its core, a theological and prophetic snapshot of music as Jewish spiritual therapy — emphasizing the unity and expressive healing that music-making can give to individuals and groups. This is a beautiful message and very needed in our time.

But this is not the Torah of all music. For if communal music like niggunim teach us one thing about ourselves, what do other types of music teach us? What does singing in a choral ensemble or Jewish a cappella group teach? What of hazzanut, folk music, or art music? Here, another personified Muse arises, and we might wonder —what do we learn from Her? This is significant to cultivated musicians of all kinds, especially cantors. It is a big question, and relates to the embodied relationships to authority that are created by musical experiences.

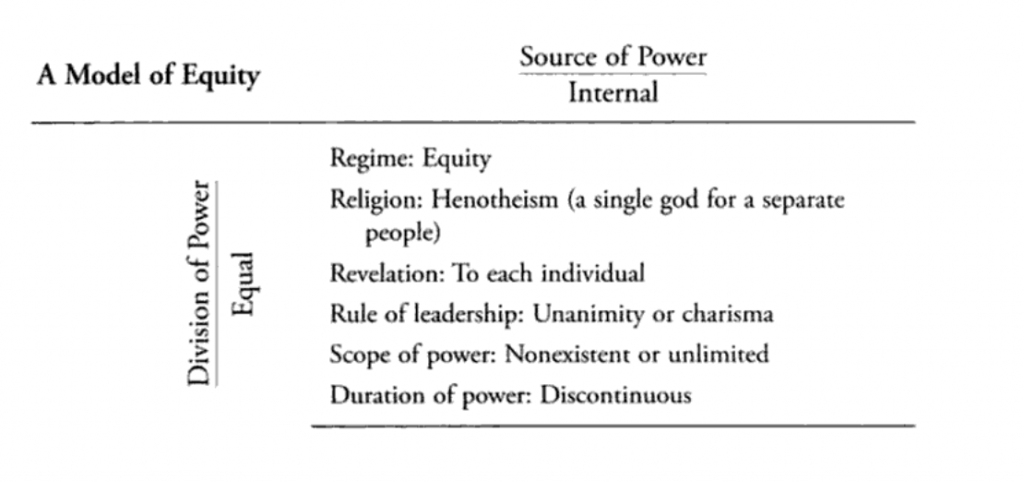

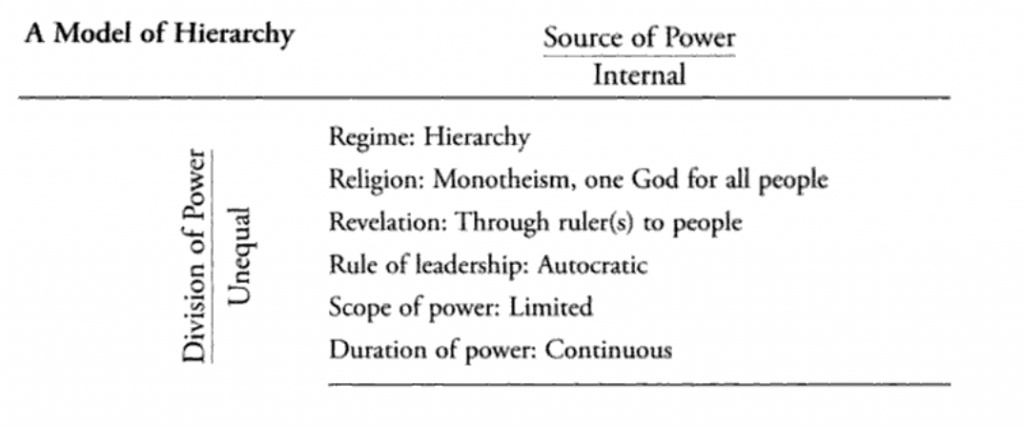

Political scientist Aaron Wildavsky wrote about the genius of Mosaic leadership in his book, Moses as a Political Leader. He describes how Moses successfully evolved the Jewish people out of unacceptable forms of leadership (slavery & anarchy), and towards acceptable ones — namely equity and hierarchy. He describes an equity as leadership by association but not authority. This contrasts with a hierarchy, which exercises leadership through limited yet unequal division of power. The interaction of these two models bears a lot on current questions of Jewish life (and it bears note that Wildavsky does not say that the Bible endorses one model over the other).

(From Moses as a Political Leader, p. 273-4)

Comparing with the Torah of Music, one can see that Joey Weisenberg teaches Jewish text and music-based spirituality primarily through the lens of equity — in which musical leadership comes from charisma and free association, not hierarchical authority. This is the leadership model that Weisenberg effectively employs as a band-member, prayer leader, and educator. It is also the theological and leadership approach that most pervades the thriving world of Hadar and other post-synagogue Jewish institutions. Even in Hadar’s expansive neo-traditionalism, halachic decision-making is determined not by a mara d’atra (a hierarchical authority), but by scholarship, referent authority, and exploring possibility within a rigorous faith and textual tradition.

The Torah of Music is, by this measure, a combination of masterful handbook of Jewish values upheld through musical therapeutics and an exaltation of the music of equity – that is musica shebe’al peh, shared through people and relationships. It is here that we should consider the continuities and contrasts presented by the incumbent leaders of both American Jewish liturgical and cultural music traditions — its cantors.

The traditional American cantorate has undergone remarkable changes in the past forty years. Whereas the initial revelations of Debbie Friedman, Shlomo Carlebach, and other sing-along prophets of Jewish musical equity were met with disdain and accusations of pandering to the “lowest common denominator,” the cantorate now contains many champions of the contemporary ethos of communal singing. The Cantors Assembly published three anthologies of congregational song in the 2000s (Zamru Lo: The Next Generation Vols I-III), and most recently issued a popular collection of the music of the independent minyanim and Jewish renewal (Shira Chadashah). Many cantors now seek to, at a minimum, hybridize their nusach and ensemble training with a congregation-centered approach to creating singing communities— if not to favor the latter entirely. The Cantors Assembly’s recently created “SongSwap” — an open, online monthly podcast & Zoom gathering for sharing effective congregational melodies — demonstrates the extent to which this trend has been institutionally mainstreamed in service of the current demands of congregational prayer.

And yet there is something inescapably different about the cantorate. As professional clergy, bound by congregations and roles in established institutions; as notenfressers guided by the revelations of composers, the direction of conductors, and the Torah of musica shebichtav (written music); and as masters of Jewish music history and pre-modern musical forms — cantors specialize uniquely (though not exclusively) in situations, institutions, and music of embodied hierarchy. It is by these (and other measures) that post-synagogue enterprises have developed allergies to cantorial culture. We are a priestly tradition in the face of therapeutic prophets, who demand that equity be central to singing experiences and difference de-emphasized. The professional cantorial model, in contrast, reads much more like the concluding prayer for havdalah, which states: Blessed are You, HaShem our God, Ruler of the Universe, who distinguishes between holy and profane, between light and dark, between Israel and the Nations, between the seventh day and the six days of creation, and,” some versions read, “between the tribe of Levi and the tribes of Israel.”

Cantors, as all prayer leaders, are meant to embody two roles — shlucha d’rachmana (representative of the Merciful One), and shlucha d’tzibura (representative of the community). Over hundreds of years, we have vacillated in how far we have leaned to one side or another. Notwithstanding the transformation of the last forty years, cantors continue to specialize in and care about music that emphasizes the vertical-in-authority (to borrow a term from Philip Rieff). This has created some major problems, but it has also allowed us to embody some equally deep truths from Torah.

In a theoretical, complementary volume to Weisenberg’s — call it “The Torah of Art Music” — one might learn another set of lessons with equally significant witness in Jewish text. One might learn about the charge of the levites over the Tanach, and the many connections between a life of music, a life of leadership, and a life of mitzvot. One might learn the depth of one Torah verse or word, and how that can be elevated and expressed in the fullness of one’s musical gifts. One might learn about the dignity of the individual spirit, and about the musical and spiritual power of a directed, united group. And one might learn about interpreting music dutifully to give honor to the musical metzaveh, the composer — not unlike the dutiful interpretation of Torah through a life of mitzvot in order to serve the True metzaveh, God.

Art music and communal music both hold valuable lessons. Aaron Wildavsky teaches that Moses’ genius was his ability to synthesize the two models of equity and hierarchy to create a strong monotheism. And so today, I believe we need an effective synthesis of these two models. The music of equity will speak to the hearts of many, but it is not the only music that has Torah to teach.

I hope that all cantors and music-loving Jews will read and embrace the message of The Torah of Music, resensitizing ourselves to each other and to our Creator through song. Weisenberg’s approach to music is certainly not the only one that can teach us wisdom, but it is probably one of the most important ones that can revive community and togetherness in an age of division. May the Holy One open our hearts with all of this Torah, and sing His love and reverence into and from our souls.

1Phillip Rieff, The Triumph of the Therapeutic. University of Chicago Press, 1987. p26.

2This is an old term for cantors who read musical notation — which, at one time, was a new phenomenon. It is notable to see how cantorial knowledge has transformed from oral apprenticeship to an increased focus on the written notation over the last hundred years.

3 Lit. “Commander” — the one who gives mitzvot (commandments).

Hazzan Matthew Austerklein is the cantor of Beth El Congregation in Akron, OH. He received his cantorial investiture and Master of Sacred Music from the H.L. Miller Cantorial School at the Jewish Theological Seminary. He has lectured and mentored cantorial students across the non-orthodox world, including at JTS, HUC-JIR, School of Jewish Music at Hebrew College, and in the Aleph Cantorial program. He is also married to Rabbinical School of Hebrew College alumna Rabbi Elyssa Joy Austerklein, Rab’11.

Joey Weisenberg has been an instructor at Hebrew College’s Prayer Leader Summer Institute.